By Josh Kun

Daggered Liberty

Exploring the Legacy of Composer Harold Bruce Forsythe

Tell me: How do you make this music? Tell me: How does this music make you? - Harold Bruce Forsythe, excerpt from “Dissonance”

“Come with me to a music class conducted by a modern Negro musician in Los Angeles,” begins “Basalt,” an unpublished essay typewritten by Harold Bruce Forsythe in 1931. “The lesson is in the Rondo Form. The Professor discourses for an hour on the form, and the class takes notes.” The professor, Forsythe continues, asks a student in the class “who has just enough dark blood in his veins to be Dark at heart,” to play an example of the rondo form on the classroom piano. The student chooses a rondo from a Mozart sonata, and as he plays, he begins to improvise, infusing Mozart with what Forsythe calls the “Folk-Spirit” of African music which, he says, casts “the shadow of the Spiritual” over the room.1

The student’s musical improvisation inspires a critical improvisation from Forsythe on the theme of blackness and European classical music. The claims and riffs come quick. There are arguments and counterarguments, digressions and contradictions. The music of the “Dark Continent” has been marginalized for too long. Too many Black musicians abandon their “dialect” and choose instead “to speak the ugly speech of the White.” There are too many Black musicians who are “indifferent” to the Black writers Jean Toomer and Paul Laurence Dunbar and too many who don’t know who Handel is. At one point in the essay, Forsythe dishes on Black musician parties in Los Angeles, where the music was Beethoven and Bach’s double concerto in d minor. Black L.A. was ahead of the white classical curve: when British composer Frederick Delius was all the rage with white classical musicians throughout California, Forsythe scoffs, he was already old news in Black Los Angeles. Copies of Delius’ opera A Village Romeo and Juliet were always checked out from the Public Library, “in EACH INSTANCE it was drawn by one of the darklings.”

Forsythe refers to this headfirst immersion by Black L.A. musicians into European classical music as a “climb,” in which Black musicians ascend, up and away from Black traditions, and at what cost? What happens to the beauty and artistry of the Black spirituals if Black musicians leave them behind and they are not called upon, as the student does, to re-imagine Mozart? Is it, he wonders, one or the other—the African or the European—or can they co-exist as they do in the “bold modernities” of a composer like William Grant Still who made his first trip to L.A. in 1930 and who Forsythe first met in New York while studying at Juilliard.

In Forsythe’s essay, there is a veneer of critical confidence, even a formal, buttoned-up swagger, but running beneath it is a clear sense of self-torment. The Black student’s performance of a rondo in a classical music class taught by a Black professor triggers issues and debates—or better, anxieties and struggles—that had already plagued Forsythe as a young musician and would continue to trouble Forsythe’s views of himself as a Black, or “Afric,” composer, as he often cheekily put it. What role should race play in understanding the essence of musical composition and education? What role should race play in how Black composers compose and how those composers are seen by the wider classical world? How to write music that embraces what he once described as “the subtler currents of ethnic sentience”? These are questions Forsythe returned to across thousands of pages of essays, poems, letters, notebooks, bibliographies, and novels, and questions that inevitably shaped the hundreds of compositions he wrote-- all his operas, all of his art songs for piano and voice, his works for small orchestras, and the pieces he dubbed “symphonic poems.” They were questions he was never able to fully answer.

Forsythe was five years old when his family moved to Los Angeles from Augusta, Georgia. His father-- whose mother was born into slavery during the Civil War and was later buried in Evergreen cemetery in Boyle Heights-- left two years earlier, walking by foot from Augusta to Atlanta during cotton season when African-Americans were forbidden from buying train tickets. He set the family up on 31st street in what would be later be known as the Jefferson Park neighborhood in West Adams (Forsythe would later to move to homes on 35th and 36th). His father became a teamster and Pullman porter and, according to a 1997 remembrance by Harold S. Forsythe (Harold Bruce’s son), would patrol the family porch at night with a rifle to scare off white vigilantes out to terrorize the few Black families on the street.2 It was an instant reminder that while the Los Angeles of Harold Bruce’s youth was often held up as a refuge for Black Americans, the city still resonated with the violence of Southern enslavement and its afterlives in Jim Crow segregation. It was a place, Forsythe wrote, “where the Dark enjoy a daggered liberty.”

For Forsythe, music became a tool of self-fashioning, of sculpting a future of his own making.

As a student at Manual Arts High School, his talents as a pianist and composer flourished, and he penned dozens of songs, piano works, string quartets, and a fantasia for violin and piano. He studied at the William T. Wilkins Piano Academy—the first interracial piano school in Los Angeles—and went on to be a pupil of USC music professor Charles A. Pemberton. In 1931, when Forsythe was just twenty-three, Pemberton hosted a special night dedicated to his student’s compositions at Baldwin Hall on South Broadway (originally the Rialto Theater, now an Urban Outfitters). The evening featured twenty of Forsythe’s compositions, performed by three singers and the concert pianist Verna Arvey, a high school friend of Forsythe’s who would later marry William Grant Still. Forsythe was an active member of what became known as the Los Angeles Renaissance, a West Coast version of the Harlem Renaissance that produced its own vital network of Black artists, writers, and musicians who were inventing new models of identity and aesthetics. Forsythe often referred to the scene as “Afrangeles,” bustling with its own “Afrangalean Kulture.”

Throughout the 1920s and 30s, Forsythe was hyper-productive, and while his work jumped styles and forms (operas, librettos, symphonies) his comfort zone was the art song. He composed dozens of them, their titles often hand-drawn in plump balloon lettering. The music was laced with triplets, tonality-shifts, and harmonic fusions, and was frequently set to the lyrics of his favorite poets. He wrote seven songs based on poems by James Joyce, four based on the 8th century Chinese poet Li Po, and a flurry of others that drew from Henry David Thoreau, Wallace Stevens, and 17th century English poet Robert Herrick, as well as several built around poems and writing by his Black arts contemporaries Langston Hughes, Arna Bontemps, Jean Toomer and Wallace Thurman. Which is to say,

Forsythe pursued-- with tremendous intellectual capaciousness-- a bold modernity of his own, one that had enough room for the Tang Dynasty, 19th century Transcendentalism, the Harlem Renaissance, and the Irish avant-garde.

In one of his many letters to his friend Verna Arvey, Forsythe wrote that he wanted to make music that was wholly original and unbound, not “music that sounds good and is correct, and brilliant, and clever, but that is dead of any genuine urge.” Was it Forsythe’s “genuine urge,” his desire to challenge any expectation of what it meant to be a Black composer in Los Angeles, that led his music to be, as he once lamented, “held in reserve,” a “terrific flop?” It’s hard to say, but Forsythe’s assessment was indeed correct. His bountiful, challenging, and bold works were largely not performed and in most histories of early 20th century L.A. music his name rarely appears (and when it does it is often alongside William Grant Still, who Forsythe wrote about and collaborated with as a librettist on the opera Blue Steel).3

In his late 20s, Forsythe began suffering from congenital deafness and by 1940 he stopped composing. His struggles with his hearing (as well as an earlier spinal disease that impacted his posture) often led to feelings of social isolation and self-doubt. “Deaf like Beethoven and Franz, stoop shouldered like Mencken,” he once wrote. Forsythe immersed himself in reading and writing. He kept encyclopedic type-written annotated bibliographies (often grouped by subject, “Acoustics, “Primitive + Folk Music,” and “Historical Studies of National or Special Fields”) and voluminous reading lists that covered everything from Sophocles, Nietzsche, and Adam Smith to French ethnographer Maurice Delafosse’s The Negroes of Africa. There was little that Forsythe hadn’t read and even less that he didn’t have an opinion about. He published select poems, essays, and music criticism in the Hamitic Review, California Eagle (“some bad articles”), and Flash, the short-lived but influential 1920s weekly devoted to Black Los Angeles, but the bulk of his writing, including multiple novels, went unpublished. One novel, Maron-Mutra + The Wild-Man, a three-volume science fiction saga he began in the 1930s, followed the title character, “a myopic sound-eater” and “Geomancer,” who hails from the sunken continent of Lemuria as he navigates worlds populated by embodied sounds. In one passage, it’s hard not to read Maron-Mutra as a proxy for Forsythe, a musical wanderer who is soon left alone, surrounded by a royalty that would never include him:

Maron-Mutra followed the sound who easily escorted him beyond the terrible garden. As Mutra would have thanked it, it vanished, leaving the wanderer standing in the midst of a glittering room hung with showy chandeliers & having walls covered with portraits of Kings.

By the 1950s, Forsythe had stopped writing altogether and became a horticulturalist. Perhaps the soil, plants, and roses that he tended brought him a peace and satisfaction that his music and writing only occasionally afforded. He died in 1976, during an era of renewed vitality for Black composers. Inspired by the Black Power movement, a new generation had mobilized around the 1968 formation of the Society of Black Composers. “In spite of Jim Crow,” the society’s co-founder, composer Carman Moore, wrote in the New York Times, “black musicians have written and performed string quartets, concertos, symphonies, operas and concert band works all along.”4 The article was titled, “Does a Black Mozart- or Stravinsky- Wait in the Wings?”

It was a headline that would have likely driven Forsythe mad. He would have filled dozens of type-written pages in response. He would have asked, “Why does the Black composer need to meet a European standard? And what does that even mean, ‘a Black Mozart’?”5 He would have launched a barrage of critiques, quoted from dozens of writers and philosophers, and spent paragraphs on William Grant Still and Samuel Coleridge-Taylor. He would have recalled that day in the Los Angeles classroom, when a young Black pianist transformed a Mozart rondo with African-derived improvisation. He would have wondered, as he had so many times before, what does it take for a Black artist to be considered a “genius”? And somewhere deep down, in a buried place, he would have wished that his music had been heard enough for the article to have mentioned his name.

___

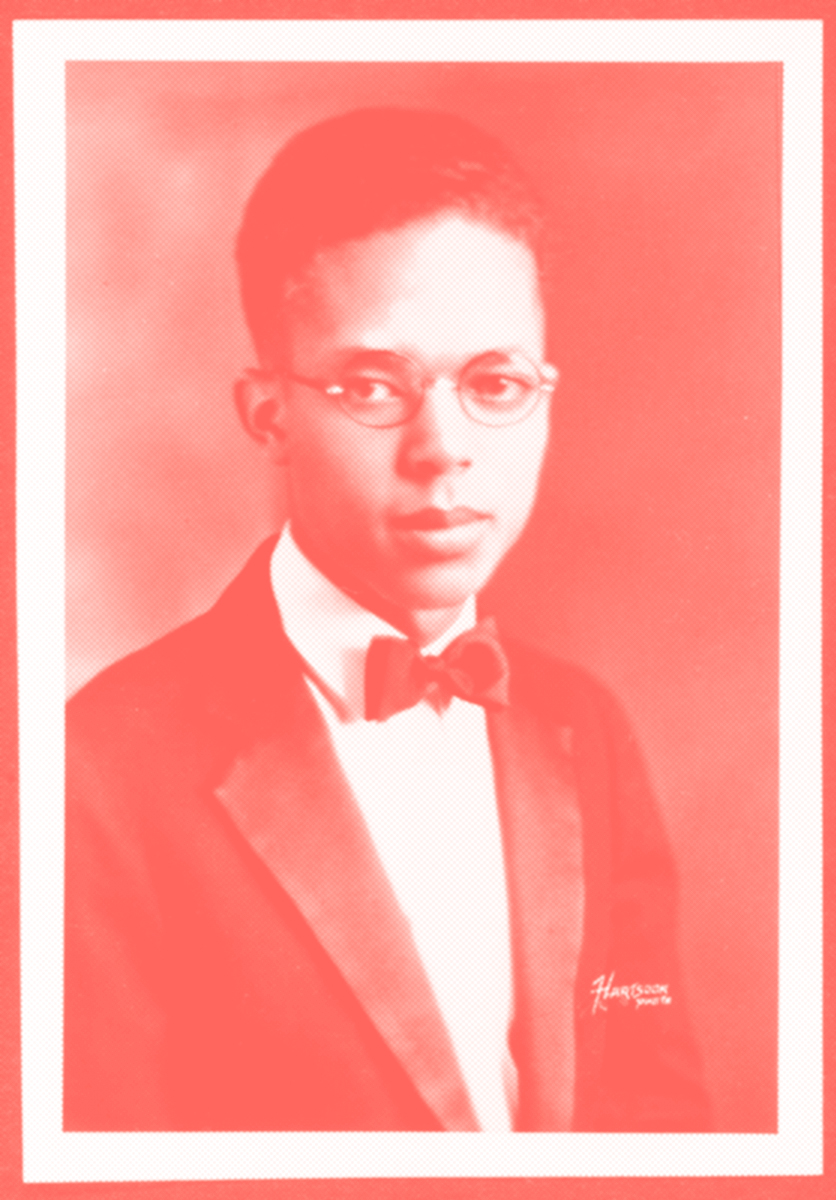

Portrait of Forsythe by Fred Hartsook. Courtesy of The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

All other images sourced from Harold Bruce Forsythe papers, The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. Reproduced with permission from the Forsythe family.

___

[1] All references to Forsythe’s essays, letters, and music are from the Harold Bruce Forsythe Papers at the Huntington Library. Major thanks to Huntington curator of literary collections Karla Nielsen for her expertise and guidance, to Harold S. Forsythe for his support of this research, to the Huntington Library for the invitation to serve as a visiting scholar, and to my Forsythe collaborator and co-thinker Dexter Story.

[2] Biographical details drawn from Harold Forsythe’s “A Remembrance of Harold Bruce Forsythe (1908-1976),” Harold Bruce Forsythe Papers, Huntington Library. As well as from Kenneth H. Marcus, “Living the Los Angeles Renaissance: A Tale of Two Black Composers,” The Journal of African American History,” 91.1, 2006, p. 55-72.

[3] Key exceptions being the scholarship of Kenneth H. Marcus and Catherine Parsons Smith, and the music pedagogy of Anne Harley, who has led recitals of and research projects on Forsythe’s work.

[4] The society’s history and the debates it engaged in also appear in George Lewis and Harald Kisiedu (eds) Composing While Black: Afrodiasporic New Music Today (Wolke Verlag, 2023).

[5] California Festival composer Marcos Balter raised similar questions in his article, “His Name Is Joseph Boulogne, Not ‘Black Mozart,’” New York Times, July 22, 2020.

____________

Josh Kun is a cultural historian, curator, and MacArthur Fellow. He is Professor and Chair in Cross-Cultural Communication at the USC Annenberg School and Vice Provost for the Arts at USC. He is currently collaborating with musician and ethnomusicologist Dexter Story on a stage performance inspired by the career of Harold Bruce Forsythe.